You are here

The Salvation Army’s Response to a Past and a Present Pandemic

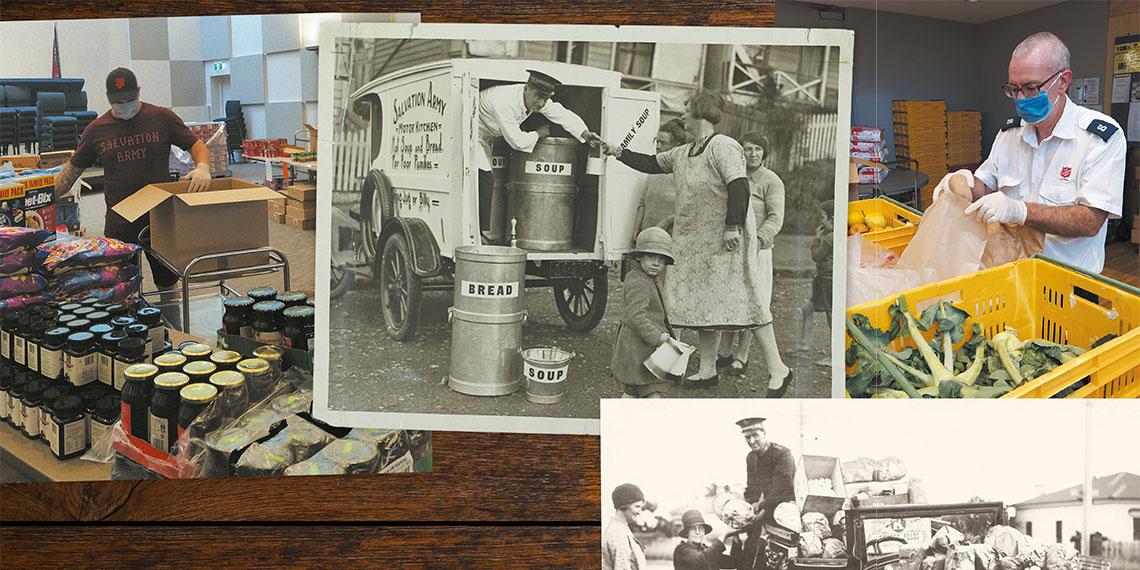

The Government’s quick response to the coronavirus was vastly different to the response of the government of the day during the Spanish influenza pandemic, which swept the globe in 1918. We look back at The Salvation Army’s response to this dark chapter in our history and compare with our current response.

The current coronavirus pandemic and the extreme measures being taken in New Zealand to contain it have caused people to draw comparisons with the world-wide 1918 influenza pandemic and its effect on New Zealand. While influenza is different from the coronavirus, the spectre of many deaths if the virus is not quickly contained certainly haunts the New Zealand Government at present.

The 1918 pandemic arrived in New Zealand just as the First World War was drawing to a close and in its wake left about 9000 people dead in two to three months. Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Rice of the University of Canterbury has made a detailed study of the 1918 pandemic. He says the pandemic’s effect in New Zealand was magnified by a ‘complacent and under-staffed Department of Public Health’ and a slow-to-act government. The varied responses to the pandemic often meant that locals were left to their own devices in managing the outbreak and caring for the sick.

This is certainly not the case this time, with the Government ‘going hard and going early’ on the advice of pandemic specialists. This has led to economic packages being rolled out to support people and businesses and an initial 28-day national lockdown apart from essential services, as from midnight on Wednesday 25 March, something which is hoped will break the spread of the virus.

Support for people in emergencies

While our family stores may be closed during the lockdown, The Salvation Army’s emergency welfare, addiction and housing support services are continuing to serve needy New Zealanders, albeit in a modified way.

The Salvation Army also assisted where it could in 1918. Many officers at both national and local levels were diverted from their usual tasks to special service at temporary hospitals. Brigadier William Hoare, National Young People’s Secretary, was put in charge of the staff at the 105-bed temporary hospital set up in the Wellington College classrooms and gymnasium. His staff of 28 Salvationists and 22 others worked in 12-hour shifts. Mrs Captain Palmer of Pukekohe was attached to the nursing staff at the local public hospital, while in Oxford, Captain Hill became matron-in-charge of the convalescent hospital set up in the Oxford District High School.

Some Salvation Army buildings were opened as emergency hospitals for victims of the influenza pandemic. Eighty beds for convalescent women were set up in the Army’s Training Garrison at 33 Aro Street, Wellington, but the opening was delayed a few days by a shortage of staff. In Christchurch, the Salvation Army’s maternity hospital in Bealey Avenue was requisitioned as a temporary hospital, as was the Army hall at Pukekohe.

In Raetihi, Captain John Griffin ‘turned the [Salvation Army] hall into a temporary hospital and himself [became] doctor, nurse, etc’. In Marton, the Army hall was requisitioned as a mortuary and no meetings were held inside for a month. In Temuka, Captain Herbert Hawkes offered the use of the Army hall as a convalescent hospital so as to free beds at temporary hospitals in the town.

In Invercargill, Ensign Harold McKenzie served on the local pandemic response committee until he himself fell ill. In Christchurch, where the city was divided into patrolled blocks, the Linwood Salvation Army hall in Fitzgerald Avenue became the headquarters for the local block committee.

Additional support was sent to the military camps, which were hit very hard by the pandemic. Supplies of fruit and drinks were provided for the men. Butter-muslin handkerchiefs, soaked in formalin and lavender, were made and distributed to men in camp. For the worst cases, these handkerchiefs were burned at the end of the day. In mid-November Staff-Captain (Chaplain) Andrew Gray was recorded as the only chaplain on his feet at Trentham Camp. His tasks included meeting wives whose husbands had died in camp before they could reach them.

Then there were the funerals. On Sunday 17 November the Wellington City corps officer, Staff-Captain Fred Burton, spent the whole day at Wellington’s Karori Cemetery conducting 17 funerals. He continued with burials at the cemetery the following day. Burton also arranged for a Salvation Army band to play hymn tunes in the streets and at several institutions, which was appreciated by the sick and bereaved.

The need for prayer and financial support was not overlooked. In November, the War Cry asked people to pray for sick comrades, the bereaved, as well as doctors and nurses. In December, the territorial commander established divisional finance boards with the direction that they give requested assistance ‘without any delay whatever’ and ‘without reference to National Headquarters’. He particularly specified that children in distress should be cared for until other arrangements could be made.

The effect on the Army internally

The current national lockdown has meant the postponement of the Army’s annual Red Shield Appeal, the cancellation of all indoor meetings and activities for the foreseeable future and the cancellation of Easter Camps and other youth activities.

In 1918 the influenza pandemic also seriously affected the Army’s operations—with people unwell, reduced or abandoned corps programmes and officers were reallocated to fill gaps left by sick officers. At one stage at least 20 officers and employees—out of a staff of 77 at territorial headquarters—were unwell, while Petone Corps reported that ‘practically every [Salvationist] home’ had been affected. There were similar reports from Stratford and Marton Corps.

Salvation Army institutions were affected by the pandemic. In November, the Army’s home for inebriate men on Rotoroa Island had up to 40 inmates unwell at a time, plus officer staff and the doctor. The Bethany Maternity Hospital, the Paulina Women’s Rescue Home and the Men’s Prison Gate Brigade all reported staff and residents suffering from the pandemic.

Government regulations aimed at containing the pandemic called for the closing of all public halls and meeting places for four or five weeks in November and December, but this was not always observed. Some indoor meetings were still held, one exception being on Sunday 17 November when health authorities allowed the Wellington City Corps to hold an Armistice thanksgiving service. Onehunga and Hamilton Corps cancelled weeknight meetings but still held some Sunday indoor services during the pandemic.

Open-air services were often held in lieu of cancelled indoor meetings. New Plymouth Corps held its Sunday meetings at Marsden’s Hill, while on one Sunday, the Christchurch City Corps held open-air services at the Montreal Street Bridge, the Square, Hereford Street and in front of the Victoria Street citadel.

Promoted to Glory

At the time of publication, there have been 12 deaths nationally with a link to coronavirus. Also, the virus has repercussions for older people, not so much younger people, but in 1918 it was far different, both for the country and for the Army and its people.

The War Cry reported on Salvationists who were promoted to Glory and those who had lost non-Salvationist family members. From War Cry reports, it seems that at least 30 Salvationists from 20 corps died as a result of the pandemic. A more accurate figure is not possible, as the reporting of promotions to Glory in this period was not always accompanied by the cause of death. Corps affected included Invercargill (four deaths), Palmerston North (three) and Auckland City (two).

Among the younger Salvationists promoted to Glory was Corps Cadet Eva Mills of Woodville, who died on 13 November aged 18; Myra Avenall, aged eight, daughter of Adjutant and Mrs William Avenall of Dunedin City Corps; and Fred Brown, aged 11 of Whangārei Corps, the eldest son of Bandmaster and Mrs Brown. Representative of older Salvationists who died at this time are Sister A. Janes (New Plymouth), Bandsman James Voitrekovsky (Palmerston North) and Sister Dorothy Lovett (Temuka). In one particularly sad case, Sister Mrs Kendall of Petone Corps died, leaving a husband, a six-week-old daughter, a three-year-old son and a seven-year-old daughter.

Three officers died in the pandemic. Adjutant Edith Chapman, matron at the Auckland People’s Palace, died on 19 November; Captain Alfred Kemp, aged 30 and a medical orderly at Featherston Military Camp, died on 15 November; and Lieutenant Myrtle Bradley, aged 27 and stationed in South Taranaki, died on 15 November 1918. Bradley had been an officer for barely a year, while Kemp left behind a wife and a nine-month-old baby son.

Aftermath

By early December, restrictions on public meetings were being relaxed, which meant that regular Salvation Army meetings and routines could be resumed and the temporary hospitals were being disbanded. Some corps held memorial services for those who had died in the pandemic and for whom public funeral services were not held. But given the number of deaths, there can be no denying that the pandemic, coming as it did at the end of the war, had a long-lasting effect both on New Zealand and on The Salvation Army.

By Major Kingsley Sampson

Major Kingsley Sampson is the editor and contributor of the book: Under Two Flags: The New Zealand Salvation Army Response to the First World War, which was published last year by Flag Publications. This article is based on chapter 13, titled: The Salvation Army and 1918 Influenza Pandemic.