You are here

Restoration and healing as guiding principles in criminal justice

Human beings are biologically and (perhaps, therefore) culturally oriented to community: we flourish best in the group. Crime is often an outcome of alienation[i]. The offender, someone disconnected from their community, experiences a ‘problematic separation of a subject and object that properly belong together’[ii]. We see powerlessness, meaninglessness, isolation, and self-estrangement among offenders abetted by the absence of pro-social norms. Unfortunately, the philosophy and principles on which are based our criminal justice policy often amplify the alienation of offenders, those most in need of reintegration.

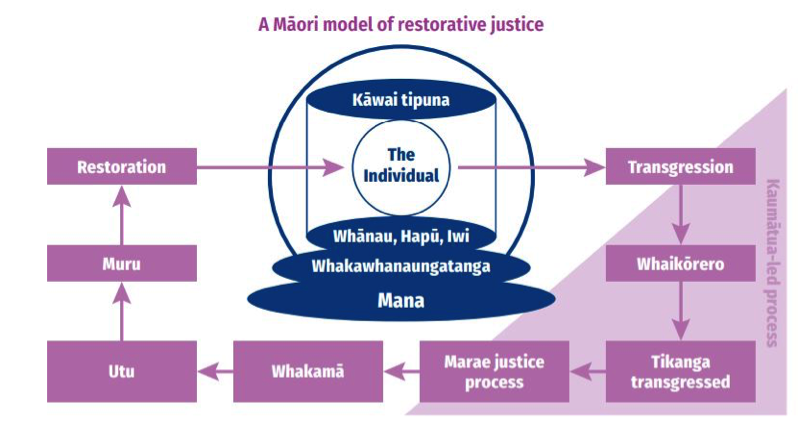

Something can be learnt from Te Ao Māori where the substance of proper social functioning is based on three dynamics: vertically, Māori understand themselves in relation to kāwai tīpuna (the ancestors); horizontally, as belonging to kin groups; and intrinsically, as the holders of mana. Each individual has the obligation to safeguard theirs and the collective mana. The key organizing value is whanaungatanga or relationships.

In Te Ao Māori, when a crime occurs, the objective is to seek the restoration of relationships. The parties, within their kin group, enter into whaikōrero to ascertain if tikanga has been transgressed. It is crucial that agreement is reached as to the exact value of the transgression and the intentionality of the act; in other words, whether the offence caused was deliberate. It is on this basis that decision-making can proceed because the specific act of restitution should be based on the specific offence: the notion of muru which prioritises proper restitution in order to achieve utu, or the rebalancing and reharmonising of relationships.

Processes of muru and utu are led by kaumātua and supported by the kin group on both sides. This ensures that, through their insight around human behaviour and motivation, kaumātua have the skills to lead the inquiry and are assisted in their task by the collective wisdom and experience of the kin groups. Collectively, this enables the accused to come to appreciate the specific tikanga that has been transgressed and, because he or she can experience whakamā (shame and remorse), is led to a place of genuine repentance and desire to make restitution. Because the outcome is arrived at through the involvement of the collective and grounded in genuine remorse, the utu, enabled by the muru, is accepted as final resolution of the matter: the guilty person resumes their rightful and full place as a member of the community, unencumbered by long-lasting guilt[iii].

Models of justice that are gaining momentum in western societies due to their effectiveness (such as these restorative justice models) reflect the essence of these practices. Fundamental to the desired goal is the restoration of proper relationships as the basis for peace, harmony, and wellbeing. This is firmly understood as entailing the rights and responsibilities of all individuals as bearers and conduits of mana and their duty to protect the resources of the natural world.

Mana gives rise to an acknowledgment of personal dignity, respect for the self and the other, and the duty of reconciliation and restoration. This is achieved by restitution for harm or damage so as to restore the dignity of all concerned and reestablish the maintenance of collective resources. The transgressing party participates in a process of community-owned decision-making grounded in a collective insight into human nature that promotes genuine remorse and a desire to make reparation.

Through this, the pain of the aggrieved party is acknowledged and healed, their resources replaced, and their human dignity restored. By so doing, the accused is released from their culpability and freed to participate in full in the activities of the community unburdened by any residual guilt or shame. Each party—and their community—is made whole and the broader tikanga that determine relationships and the use of resources are restored and reaffirmed.

Certain principles can be drawn from here. The foundation of proper societal functioning is relationship in the context of inter- and intra-community peace. All individuals are seen as having a responsibility to promote peace, in other words, they are all kaitiaki (guardians) of the public peace. The judicial process is exploratory and inquisitorial rather than accusatory and adversarial. The objective sought is genuine remorse determined by the community as a whole and the outcome is considered to be met when accurate restitution is made and parties feel recompensed.

A model exists here for the reform of our criminal justice system. In research carried out by Victim Support New Zealand[iv], Dr Petrina Hargrave found that what is craved by victims is the recognition of a wrong having been done and awareness of its impact on the victim. This produces evidence of remorse, and an undertaking of accountability by the perpetrator. Victims are able to move on and seek closure, knowing the pain caused to them has been recognised.

By Vincent Wijeysingha, (Social Policy Analyst, Social Policy and Parliamentary Unit).

This Think-Piece is adapted from the author’s report, Reconsidering the Aotearoa New Zealand Criminal Justice Policy Model.

[i] Smith, H. P. & Bohm, R. M. (2008). Beyond anomie: Alienation and crime. Critical Criminology, 16(1), 1-15.

[ii] Leopold, D. (2018). Alienation. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition). California, United States of America: Stanford University. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/alienation/.

[iii] Some useful resources to learn about Māori models are He Hīnātore ki te Ao Māori: A Glimpse into the Māori World, available at http://tmoa.tki.org.nz/content/download/762/7209/file/HeHinatoreKiTeAoMaori.pdf; The Woven Universe: Selected Writings of Rev Māori Marsden; Cleve Barlow’s Tikanga Whakaaro: Key Concepts in Māori Culture; and Prof Khylee Quince’s chapter, Maori and the criminal justice system, in Criminal Justice in New Zealand, edited by J. Tolmie & W. Brookbanks.

[iv] Hargrave, P. (2019). Victims Voices: The Justice Needs and Experiences of New Zealand Serious Crime Victims. Wellington, New Zealand: Victim Support. Available at https://victimsupport.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/VS-Victims-Voices-Research-Report-Aug-2019_WEB-PRINT.pdf